When you say “Celt” to people they think of Ireland or Scotland or maybe Asterix the Gaul, but the Celts were much more widespread across Europe than that, and the definition is much looser than people realise. Ancient Celts are generally defined as speaking one of the variants of the Celtic language, an Indo-European language, and by a cultural package of art styles and iron-working technologies. Modern genetic studies on grave sites haven’t found some specific “Celtic” marker, they’re just local Europeans with a mix of ancestors, albeit with a good chunk of R1b markers from the Yamnaya nomads who brought the Indo-European languages to Europe from the Steppes, as you might expect (and as is still common in Western Europe).

One of the earliest centres of Celtic culture was in fact in the Austrian Alps around Salzburg. Known as the Hallstatt Culture due to first being identified from burials in that area, it spanned the transition period between the Bronze and Iron Ages roughly three thousand years ago. It’s very difficult to precisely carbon date artefacts from this era however, as the phenomenon known as the Hallstatt Plateau also known as the First Millennium BC Radiocarbon Disaster meant cosmic rays and changes in solar activity at this time caused dramatic fluctuations in the amount of radioactive carbon fourteen in the atmosphere and stops the lab tests from working properly.

There are three types of carbon on earth. Carbon twelve and thirteen are stable, but carbon fourteen is unstable and radioactive, created by cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere. When plants and animals are alive, they take in carbon from the air or food in the same proportions as the world around them. Once they die however, the carbon fourteen slowly decays and disappears. Every 5700 years the amount of carbon fourteen halves, so scientist can test the proportions of the different carbon types in organic material, and compare how much carbon fourteen is left to date the specimen. Of course it’s not quite that straightforward: events like volcanic eruptions, atomic explosions and solar flares increase the amount of carbon fourteen, but the Industrial Revolution and its heavy usage of fossil fuels also lowered the atmospheric levels. So scientists use complicated calibration techniques to account for these things.

However in the Hallstatt Plateau era, the levels are so erratic that every item tests as 500 BC whatever its real age. This means that archaeologists have to rely on the older methods of inspecting tree rings and comparing pottery styles to try to date sites, which is especially frustrating as it was a time of rapid social and technological change in many regions of the world.

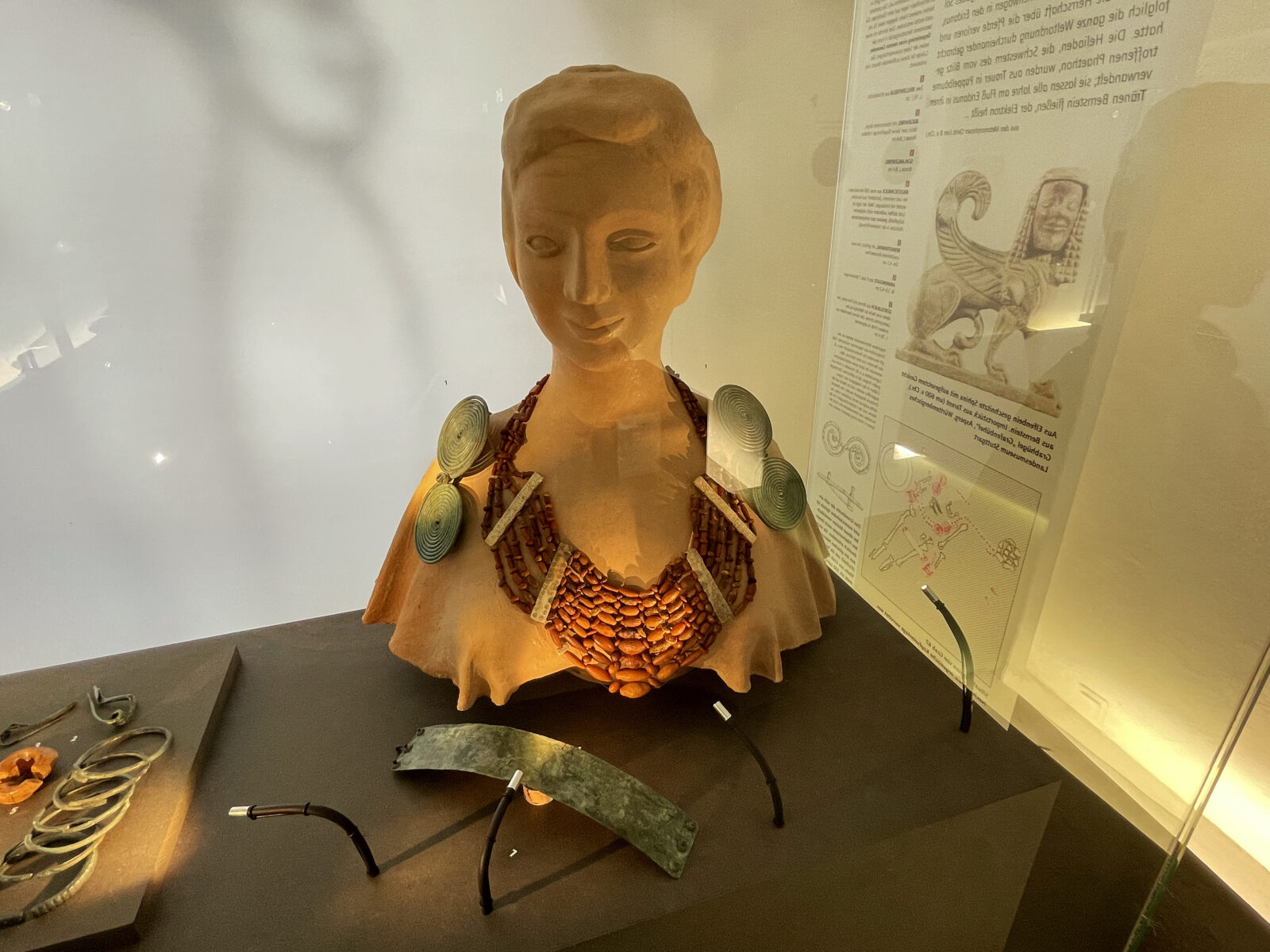

The Hallstatt Culture people of the Salzkammergut were extremely wealthy from the salt trade and left behind lavish grave goods decorated in a distinctive geometric style. They lived in fortified villages on hilltops, some of which were so large they can be described as the first cities in the region, with impressive monumental buildings and burial mounds. They traded long-distance to the Mediterranean and Baltic, and had expensive metal armour and weapons and lavish gold jewellery and metal sculptures of animals. Their art style later spread west to Britain and Ireland.

There is also an excellent museum in Hallein that focuses on two intertwined things: Ancient Celts and salt-mining.

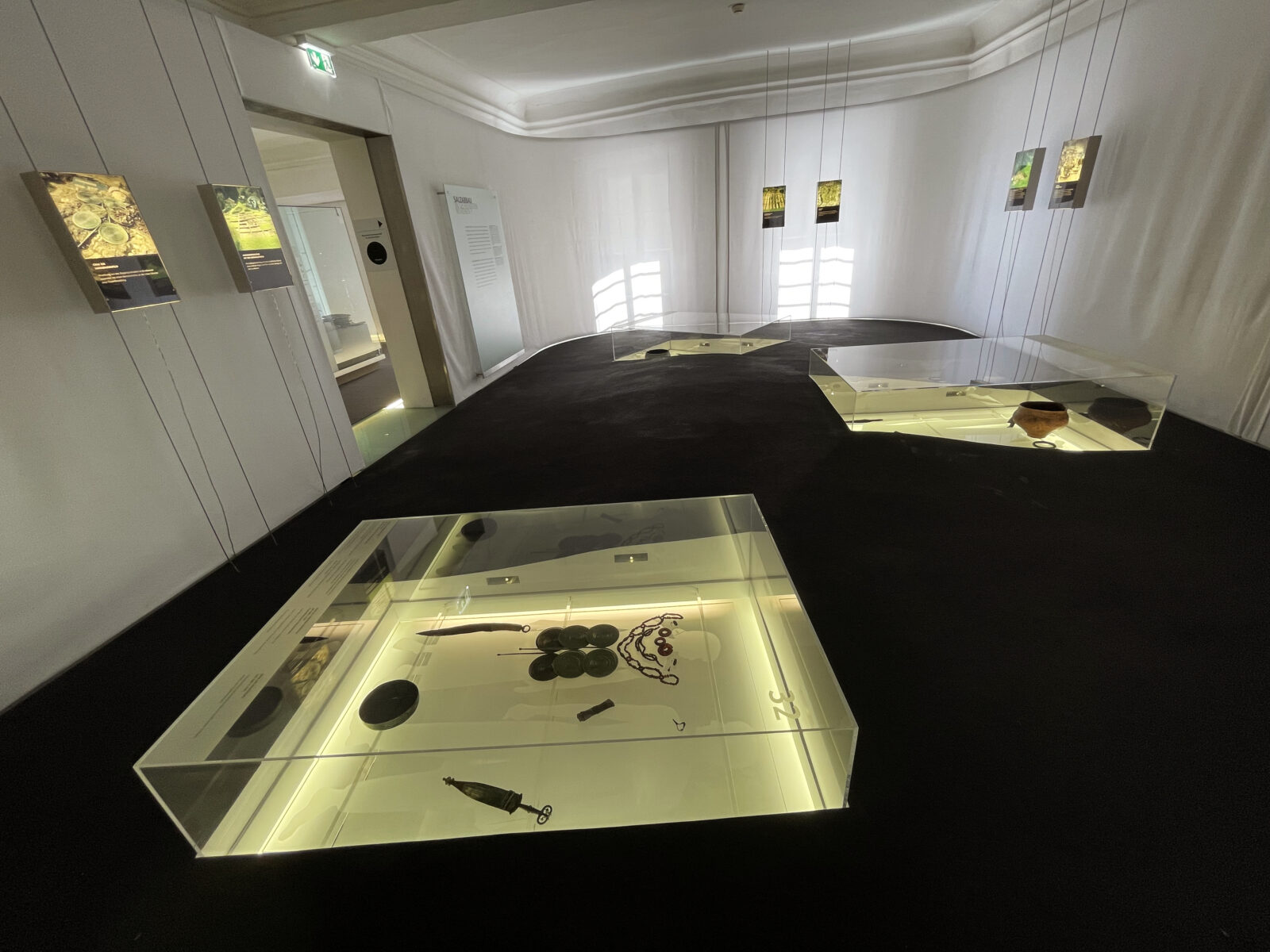

In the first room, artefacts were displayed in this 3d timeline

Trumpets

Children were invited to dig up fake bones from this sandpit. I would have been absolutely all over this as a kid.

Opfer does mean sacrifice or victim (and comes from the same root as offer in English), but it’s also German slang for loser, so the label on this box made me laugh.

Assorted grave goods

I really liked this wooden topographic map of the local area.

What happens in the “witches’ wall field”?

A Roman legion standard. Like the one the Germans stole from them at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest, where the Romans got their arses sorely kicked.

The Celts were known for their love of patterned fabrics.

Replica of the ancient shoes

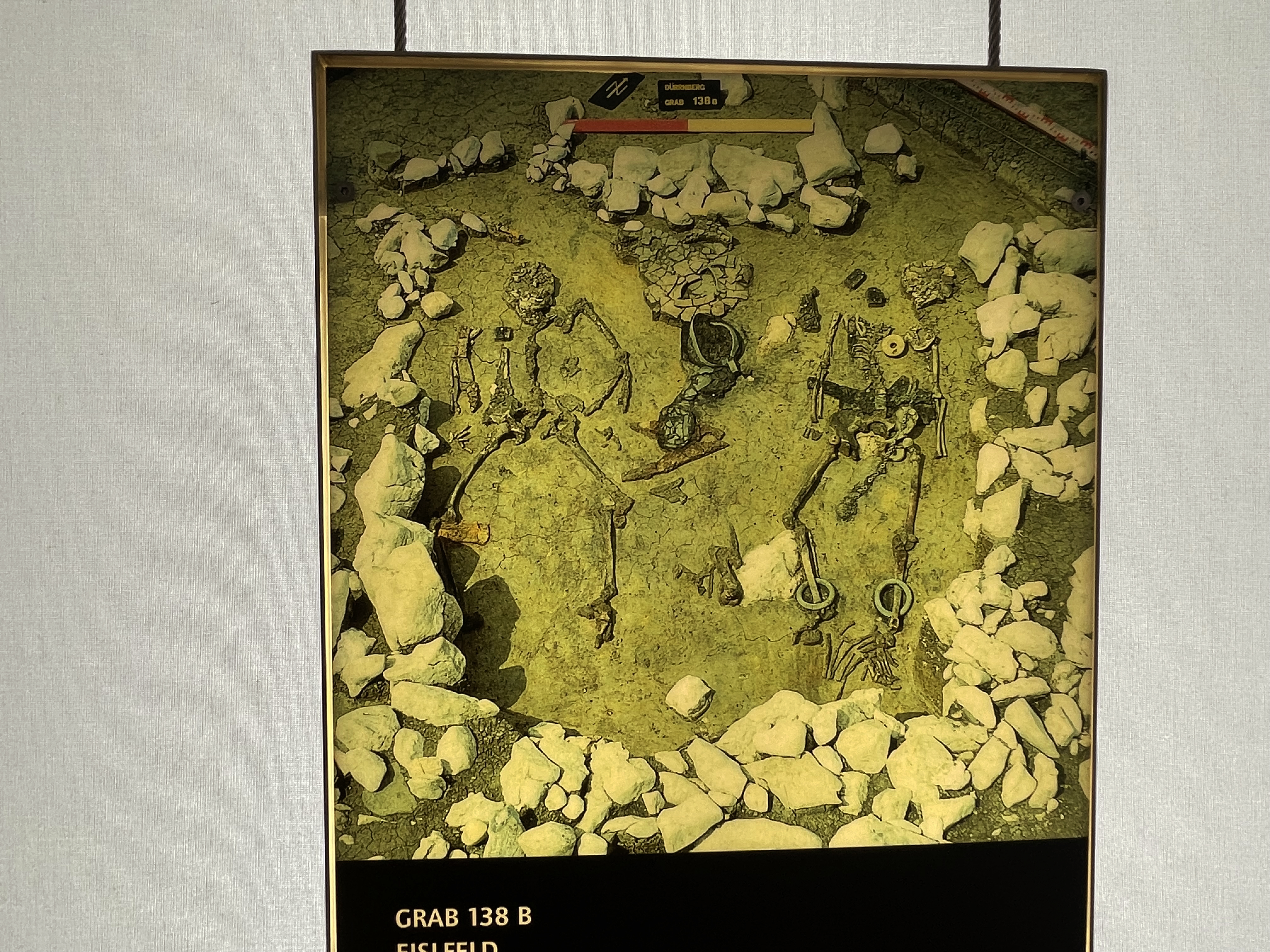

Grave goods of a couple laid out the same way they were found

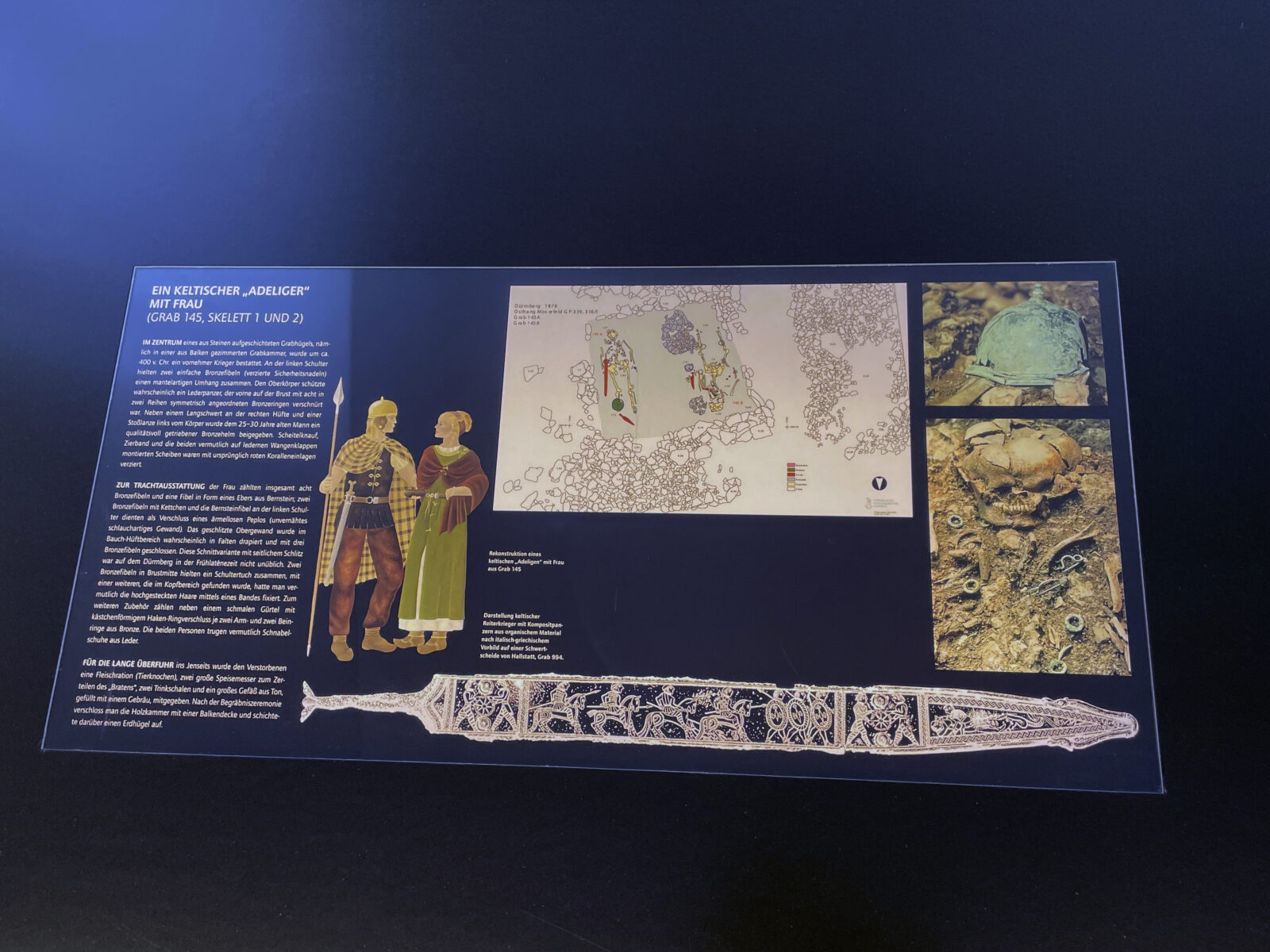

Quality waxworks of the couple from the grave.

Room recreating the topography of some of the museum finds.

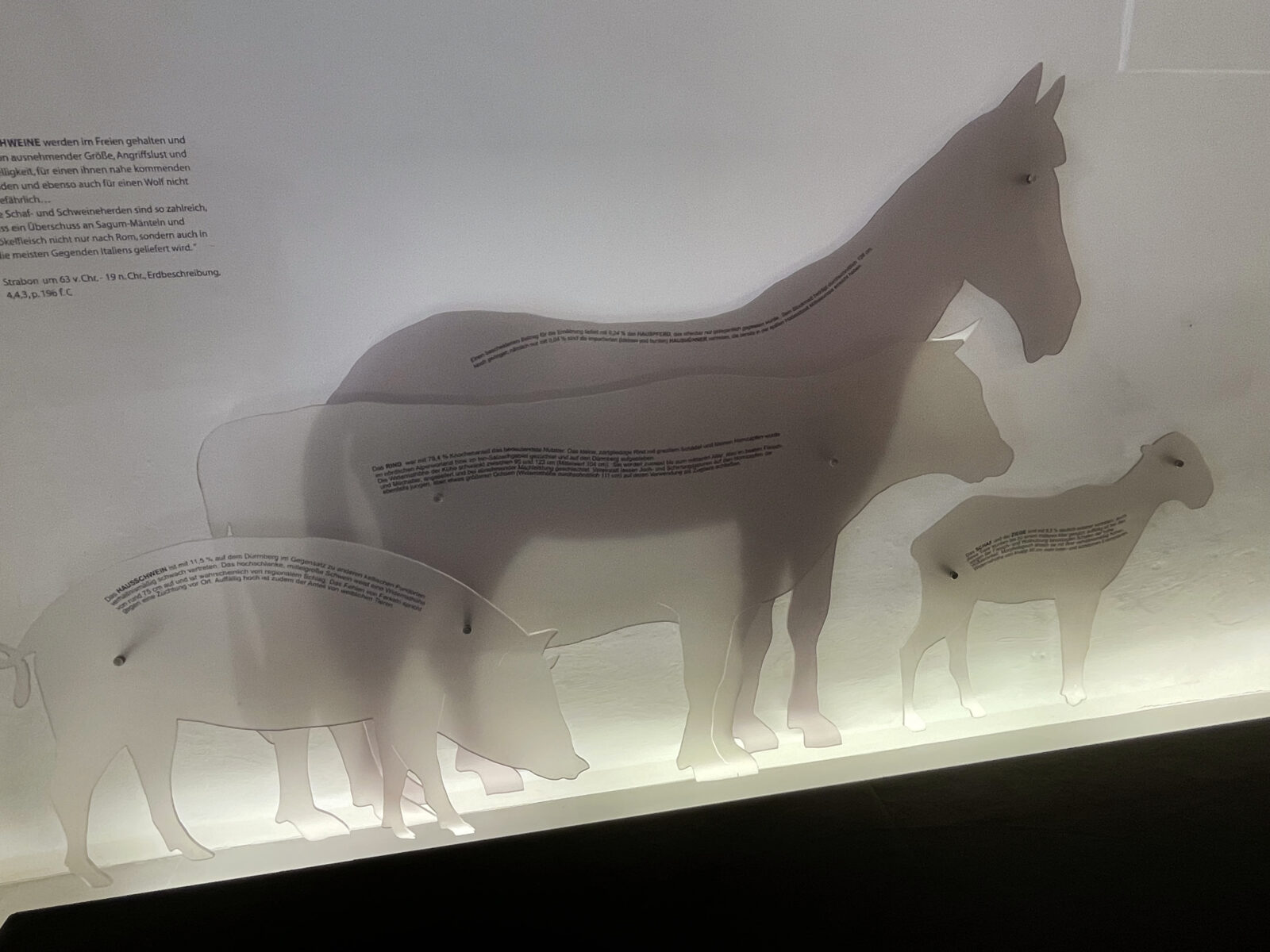

Silhouettes of the physical size of Iron Age farm animals. They were all significantly smaller than today. The sheep was about the size of a medium sized dog. The cow was about 90cm tall. Modern cows are around 1.5m.

The other topic of the museum was salt mining. Here’s a prehistoric salt miner testing his wares

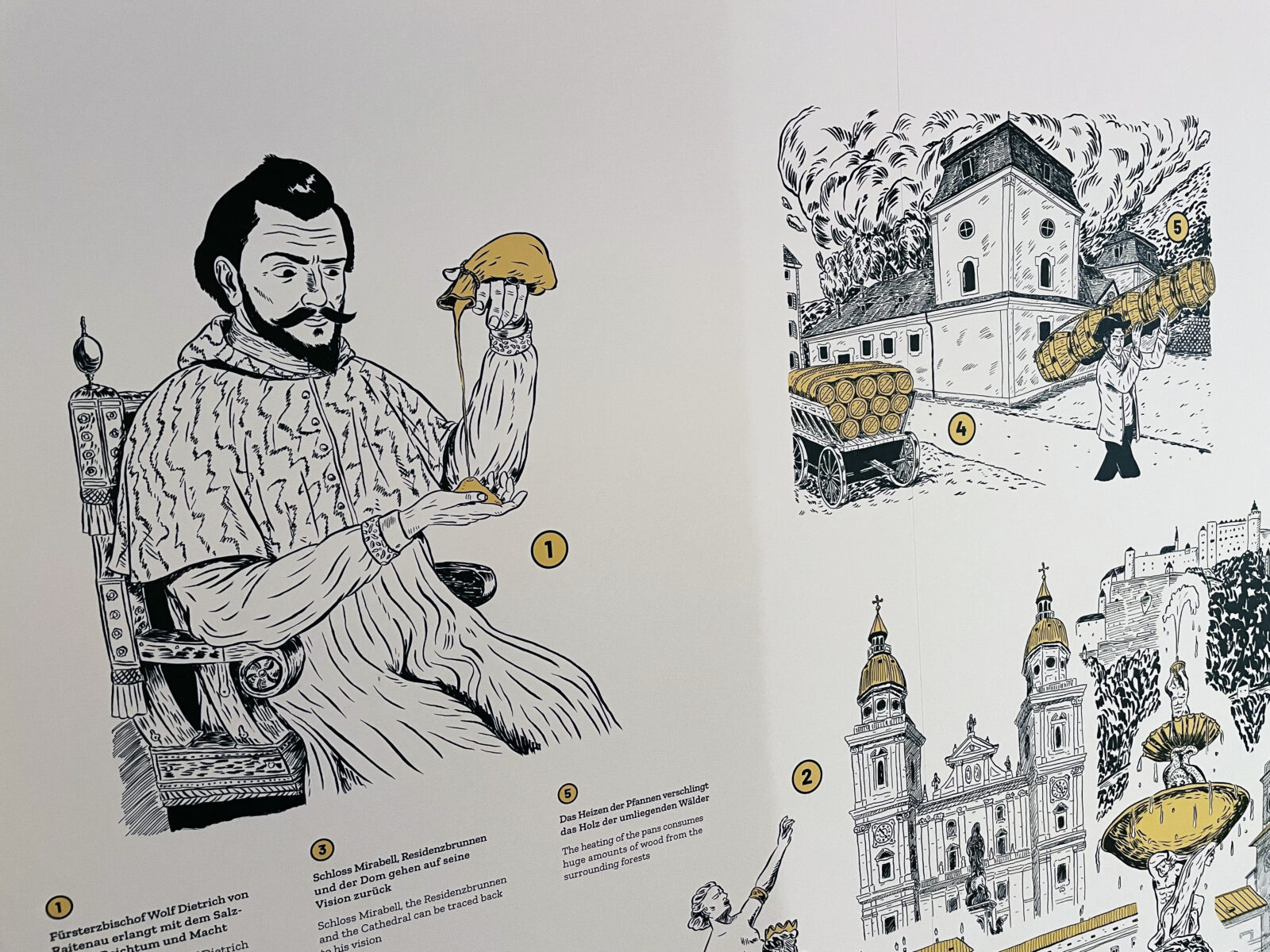

Salt transportation. Salt mining ceased after Austria became part of the Roman Empire, and it was easy to import sea salt from the mediterranean. It started again in the Middle Ages, and the Prince Bishops of Salzburg became immensely rich from the trade after crushing their regional rivals.

The salt was formed into pillars for transportation in these moulds

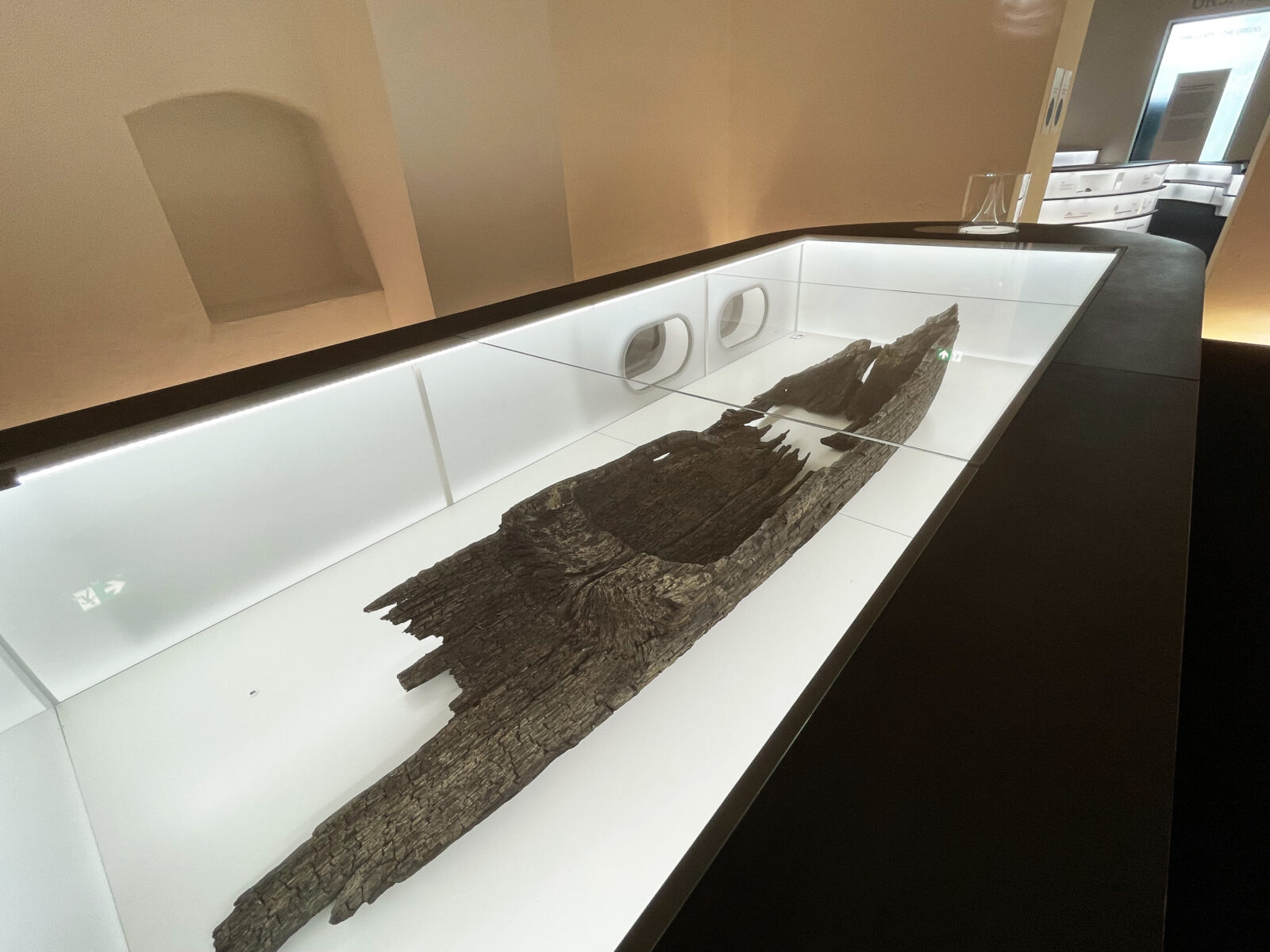

Medieval Hallein. The museum is located on the riverside where the logs are piled up in the model.

The island now has a park and community centre on it rather than a log yard.

Kachelofen heating stove. For some reason the UK rejected this much cleaner technology and kept using open fireplaces for a few more hundred years.

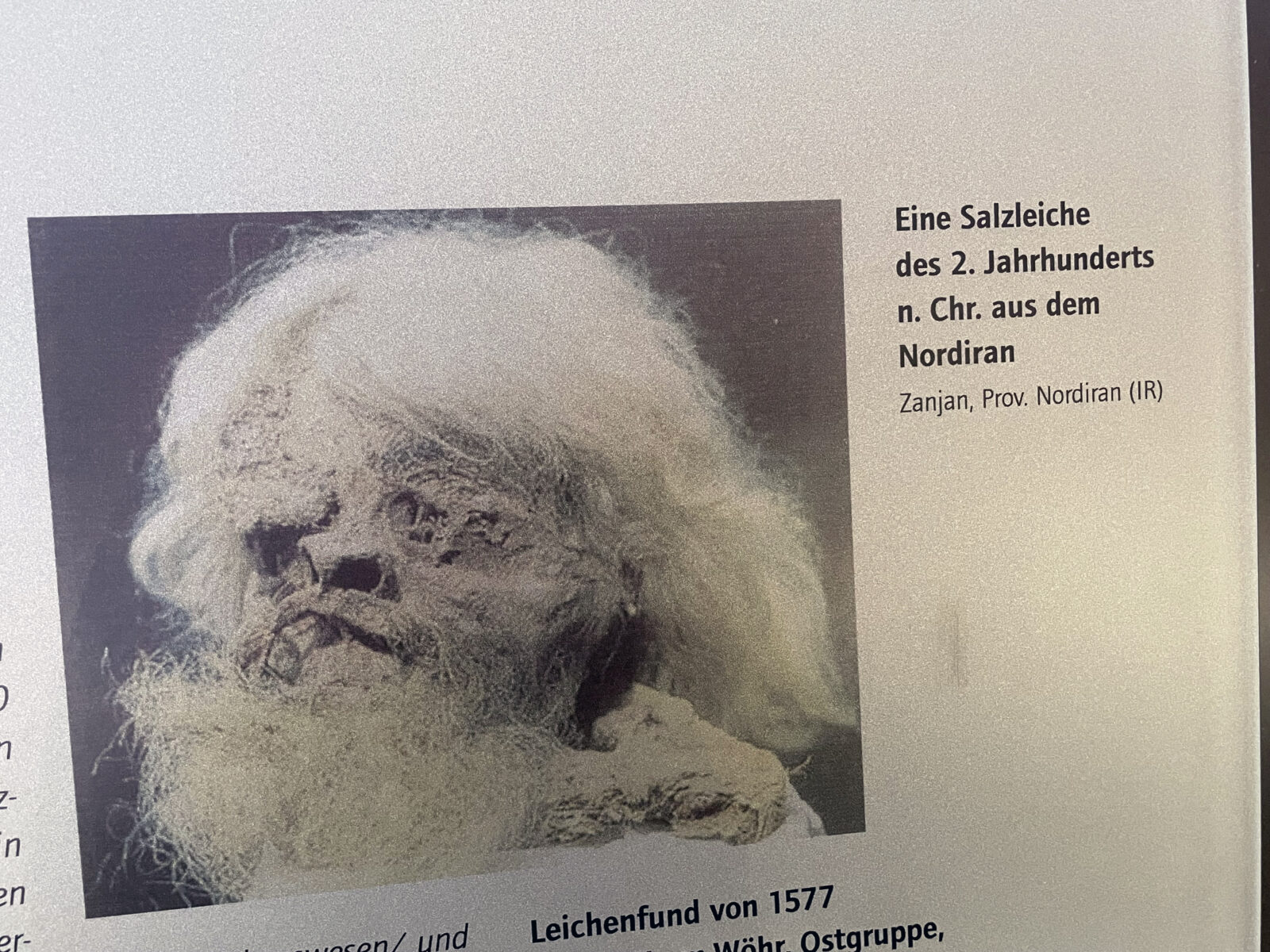

A salt mummy from Iran, circa 200 BC

A real salt mummy found in the nearby salt mine. Not an ancient Celt, but a guy from the 1600s

Outside the museum

Leave a Reply