While I was in Hallein I was determined to visit the salt mines, which have been in operation since 5000 BC. The Ancient Celts made a fortune from the salt trade. When the Romans came to Austria, the mine closed up, as they could easily import sea salt from the Mediterranean, without all the work or danger. It was re-opened in the thirteenth century however, when the now independent Prince-Archbishops of Salzburg saw a fantastic economic opportunity, which did indeed make their city fabulously wealthy (at the expense of the dangerous labour for the miners). They also sacked and burnt the rival salt producing town of Reichenhall just over the border in Bavaria. The mine closed in 1989 and became a museum, but they still extract a small amount of salt to sell to tourists.

The tour isn’t the cheapest at thirty euros, but I don’t really see the point of travelling so much for work and making no attempt to experience the unique sights of a place. When I was still living in London, I used to have recurring dreams about walking through endless tunnels of salt mines underneath Thanet where I now live. In reality the area is full of chalk caves including the famous Shell Grotto. In the dream the walls were pink and glowed like those mineral salt lamps you can buy from new age shops, which is extremely unrealistic. I have one of those lamps now, but had to put it on a high shelf after my cat decided it was his own personal salt lick, which can’t be good for him. If you dream things though, I feel you should do them, even if the real life salt mines don’t in fact glow pink.

The name of the mountain itself where the salt mine lies is straight out of Tolkein- the Dürrnberg. To get there you have to take a small bus from Hallein that winds its way through an industrial estate and around tight mountain roads before dropping you seemingly in the middle of nowhere. Hidden behind the trees however is a modern glass building marking the entrance to the salt mine.

None of my co-workers had wanted to come in the end, which turned out to be a bonus. When I arrived they asked me if I wanted the English or German tour. The German tour had just me and one woman with her two grandchildren. The English tour had a huge school party on it. So I essentially got a personal guided tour for being able to speak German, which would not have been an option with a co-worker in tow. Sometimes it pays to do things alone.

First of all before entering, we had to leave any coats or large bags in a locker, and put on white boiler suits over our clothes, to avoid coming out covered in dust. The boiler suits also had reinforced backsides.

To get into the mines you first had to ride the mine train, sitting astride what was essentially a wooden bench on wheels, like you were pretending to ride a horse on a school gym bench. Two weeks before my hip had got crushed in a malfunctioning train door and I was still having problems with it. It turned out not to like sitting on the bench train at all. I had to sit awkwardly and grip on to the bench, rather than sit in the natural position, as my leg wouldn’t quite bend to the right angle. It’s much less fun when you are concerned you are going to fall off the wooden bench train (not that it was going at all fast) because your leg locked up in a weird spasm.

The thing the journey reminded me most of however was the train scenes from Tarkovsky’s Stalker. In the film, there is a mysterious Zone, the scene of an unspecified disaster, where the laws of physics don’t quite work the same, and where it’s rumoured your wildest dreams can come true. It’s illegal to enter, but professional guides called “stalkers” surreptitiously take visitors in. The story follows a writer and a scientist who accompany a stalker into the Zone. At the beginning of the film the group evades the soldiers guarding the entrance and sneak in via an old industrial train. Tarkovsky uses the slow rhythmic clanking of the decrepit old train to ratchet up the tension, while slowly mixing in synth sounds. The start of the scene has muted sepia tones, but by the end when the spacey synth has almost completely overtaken the industrial clanking, the characters suddenly find themselves in colour, in a strange new landscape. I didn’t have any synth track accompanying me, but the speed and endless decrepit clanking of the train were pretty much identical.

To descend into the mines themselves, you slide down “Europe’s largest wooden slide”, straddling another wooden bench in the centre. It turns out this is what the reinforced thighs of the boiler suits were for. My injured leg just would not bend right to sit on it though, so I had to take some vertiginous wooden steps next to the slide instead.

Once at the bottom of the slides, we took a boat over an underground salt lake. When I was a child one of my favourite books was C.S. Lewis’ The Silver Chair. (My least favourite however was the final book in the series, The Last Battle as I very much resented being Jesused so hard). The characters embark on an underground journey clearly inspired by HG Well’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth to rescue a prince from a witch, and cross a very similar lake in a boat. The gnomes crewing the boat like to ominously repeat “many sink down, and few return to the sunlit lands” to their guests. The salt mine guide sadly didn’t cheer us up with this, instead preferring to explain the processes of salt mining which created the lake. The salt extraction process itself was arduous and dangerous in the era before machinery. I felt vaguely guilty for coming from a country with endless practically free sea salt.

The caves in the Narnia book also feature halls of sleeping mythological beasts, and a further layer deeper underground, where fresh gemstones are juicy like fruit, and there are rivers of magma inhabited by fire salamanders. Once free of the witch’s curse, the gnomes invite the children and the freed prince to visit them there, but the offer is turned down. I was always disappointed by this as the setting captured my imagination.

I didn’t see any mythological beasts or living gemstones in the Dürrnberg salt mine, but I did see the original site of the salt mummy I saw in Hallein museum, who had been replicated by a dummy.

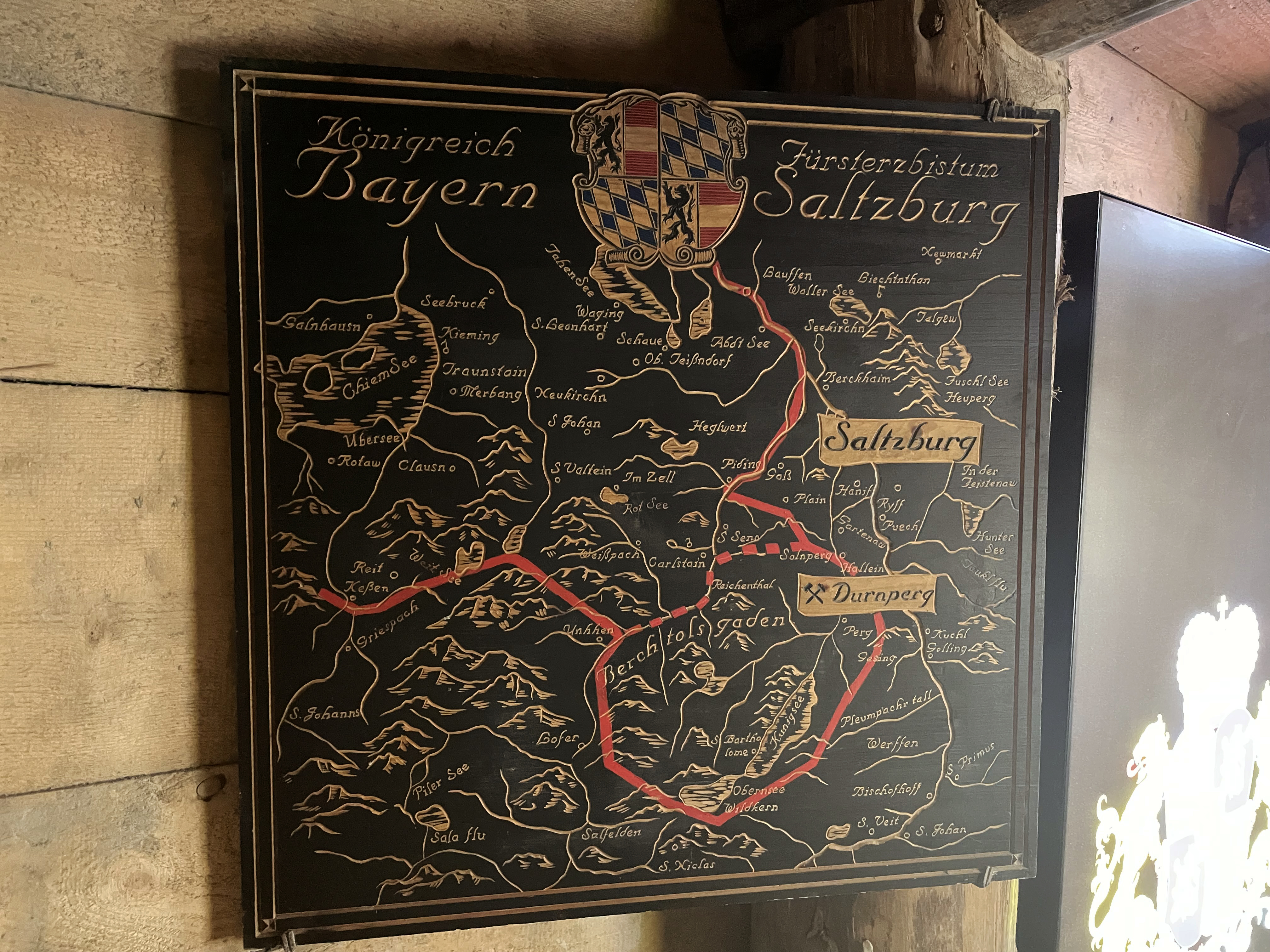

There is also a border between Germany and Austria on the Dürrnberg, which is helpfully signposted underground, in one place with modern glowing lit up flags and a copy of an airport border control sign, and in another with an antique wooden sign and map. You can also tell the difference between the sides because at one time they were crewed by different teams with different mineral extraction rights, and they used different designs of supports for the tunnels.

“National border: Federal Republic of Germany, Republic of Austria. Historical border: Kingdom of Bavaria, Prince Bishopric of Salzburg”

Here’s a map of the local area, with the border marked in red. P and B are often interchangeable in Austrian German, which is why the historical maps says “Durnperg”. People often say something that sounds like “best” for pässt (that’s fine, don’t worry about it). “Bischofshoff” is Bischofshofen.

Demonstration of all the different minerals in the groundwater there

Demonstration of the same wooden salt moulds I saw in the museum.

How a salt seam looks in the rock. The salt mine also has a very distinctive smell.

Not naturally occurring

When you emerged from the mine, there was a gift shop with every possible kind of salt-related gift and size of pink salt lamp imaginable.

Although they seem to have got the wrong country altogether for this bag. Didn’t see any kangaroo ones though.

I bought a small wooden salt scoop (which gets used daily, albeit with sea salt) and plastic topographic map of the Salzkammergut, along with a mineral sample from the mine to go in my printers tray on the wall at home, and squashed a penny in the machine to get a souvenir coin for the same display.

I then ate some chips from the café, seasoned with salt from the mine.

On the slopes about the visitor centre is a replica Celtic village arranged around a waterfall. There were no actors doing demonstrations on the day I was there, but it was still pleasant to wander round.

The thatched wooden cottages had replica furniture inside, and demonstrations of weaving, pottery and wood-carving.

The thing it reminded me of the most however was the old video game Simon the Sorcerer, with the mossy rocks, gentle waterfall and thatched cottages. I was surprised there wasn’t some soothing MIDI music or puzzles to solve. At least nobody said “That doesn’t work” at me in an exasperated voice.

Leave a Reply