They weren’t keen on you taking photos of the museum and it’s fairly dark inside, so I’ve gone with more general thoughts about Kafka.

The first time I encountered Kafka was when I was 15 or so and the local drama group I was in did a play of In the Penal Colony (yes, really). I actually read one of his books for the first time in a university German class. The class was great, we read Kafka and watched Metropolis and the Cabinet of Dr Caligari. The other students were a pain, they complained everything was “weird” and “old” and just wanted to do grammar exercises. But I loved it.

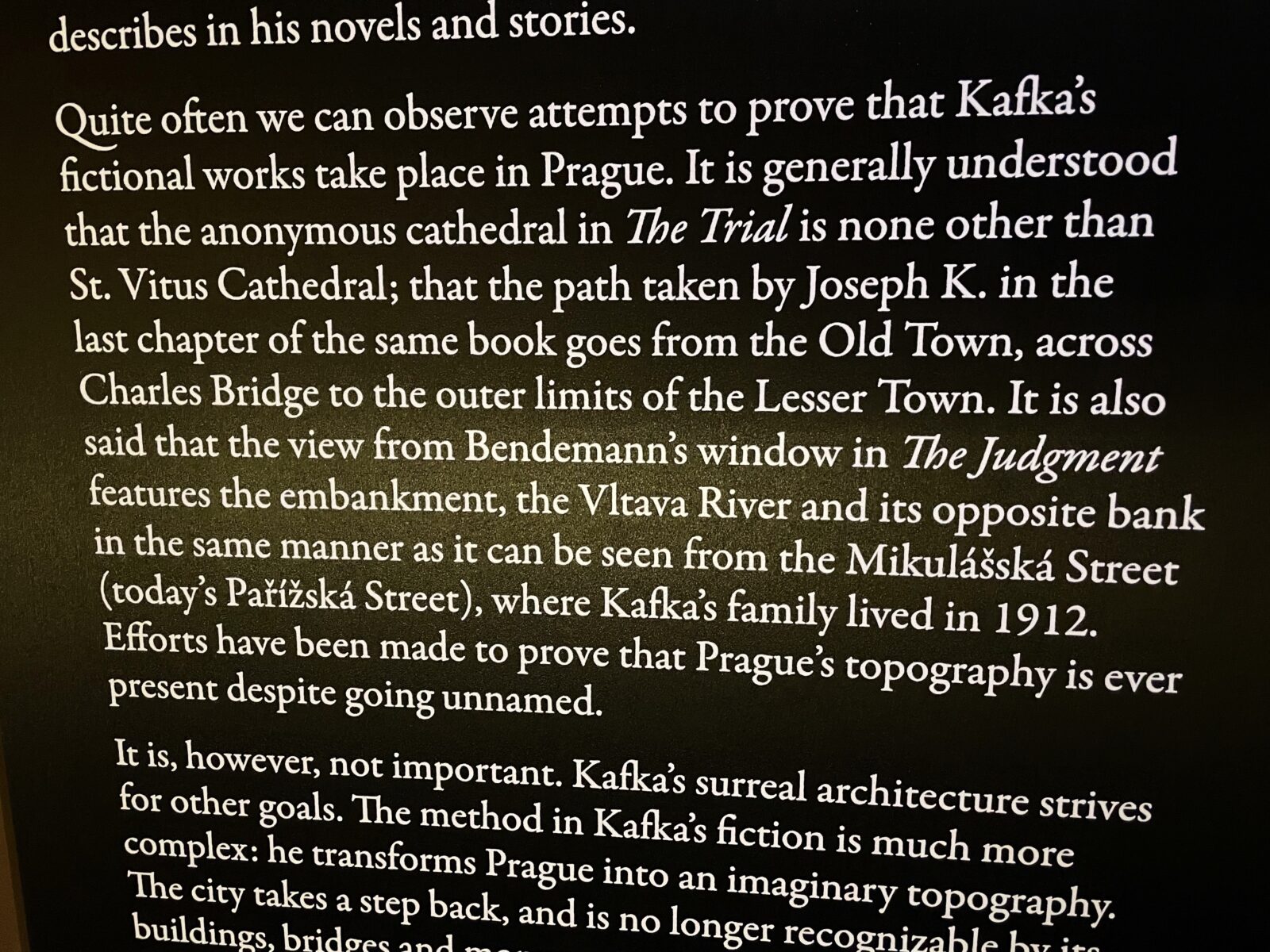

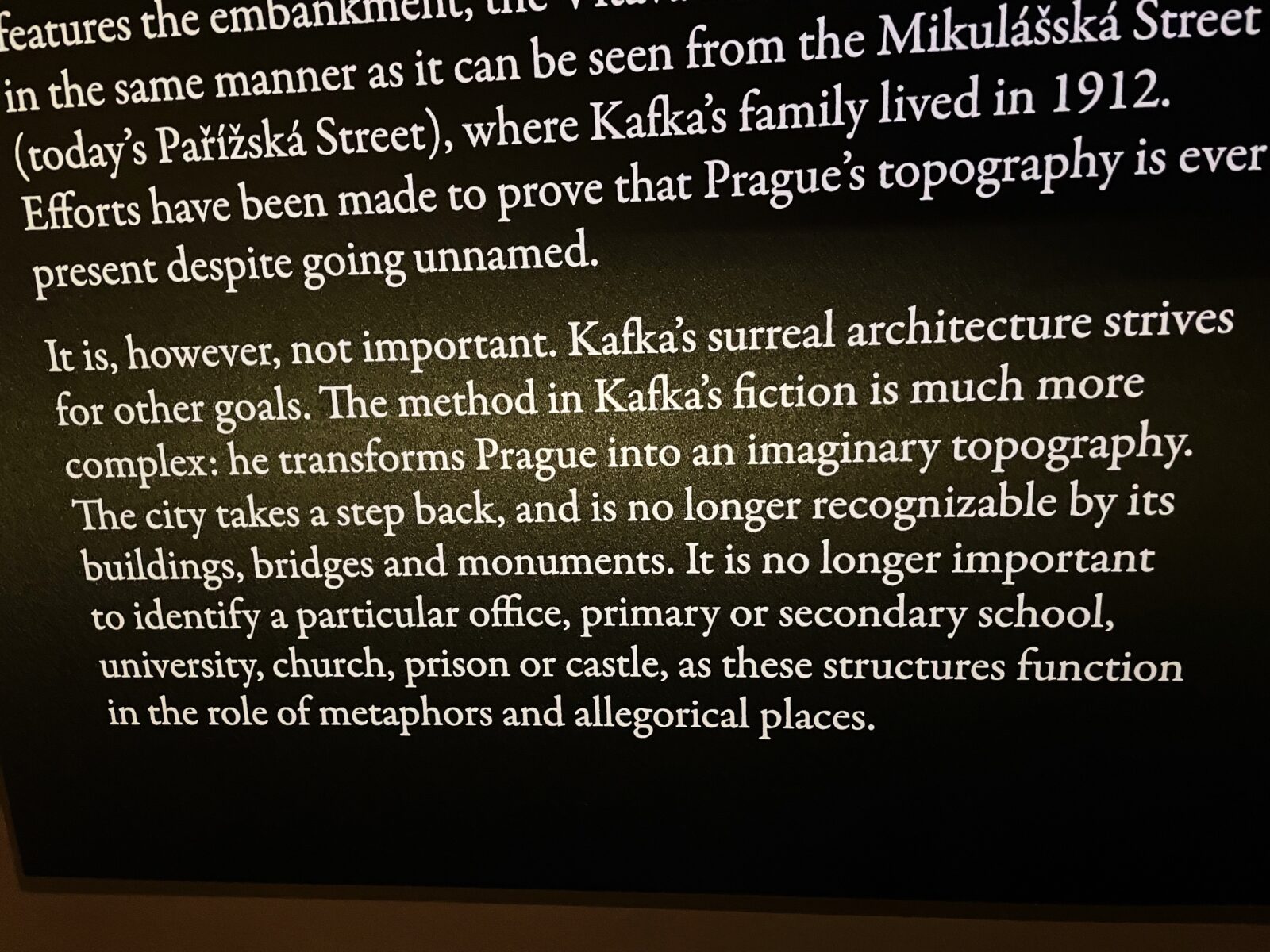

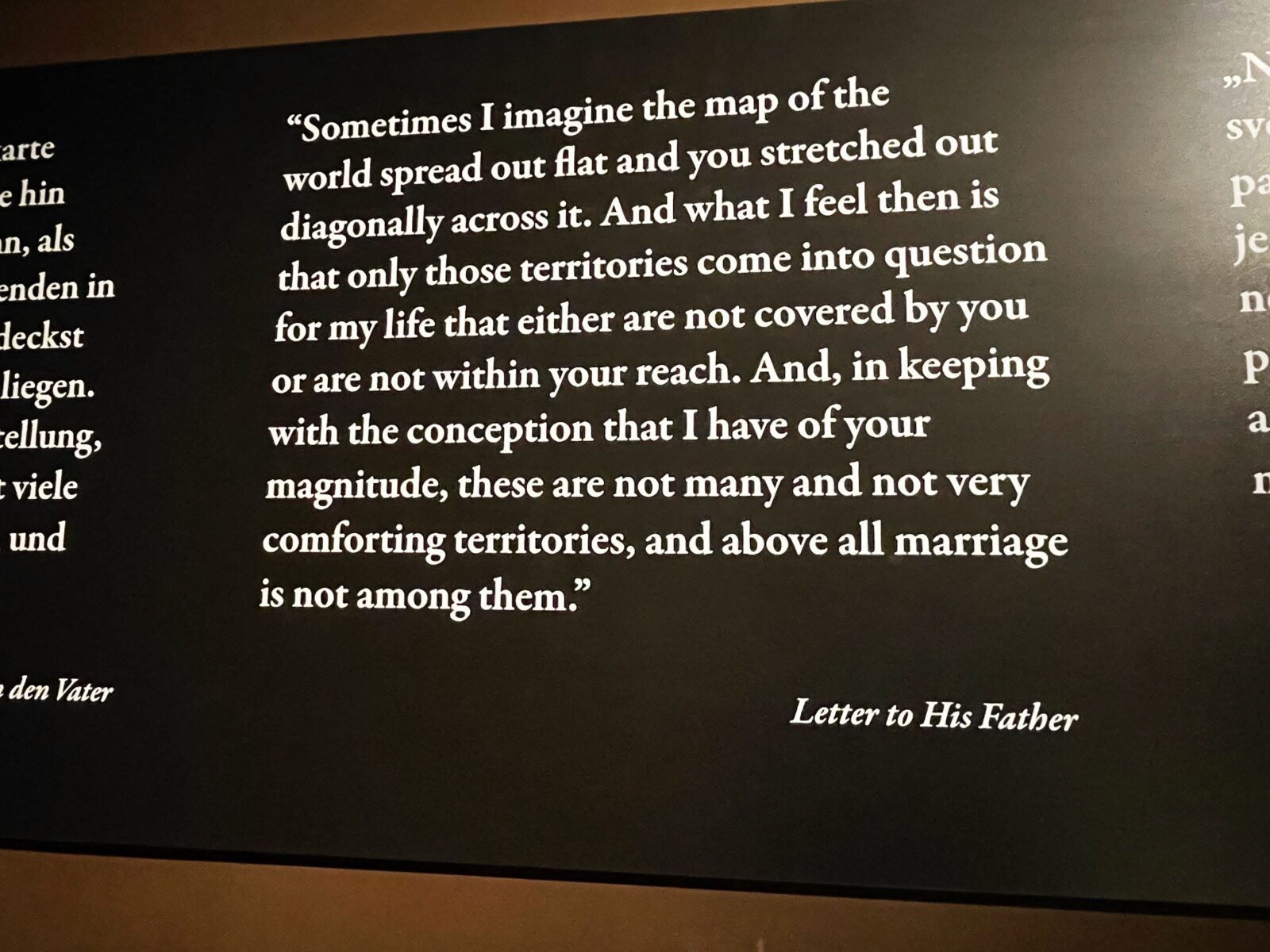

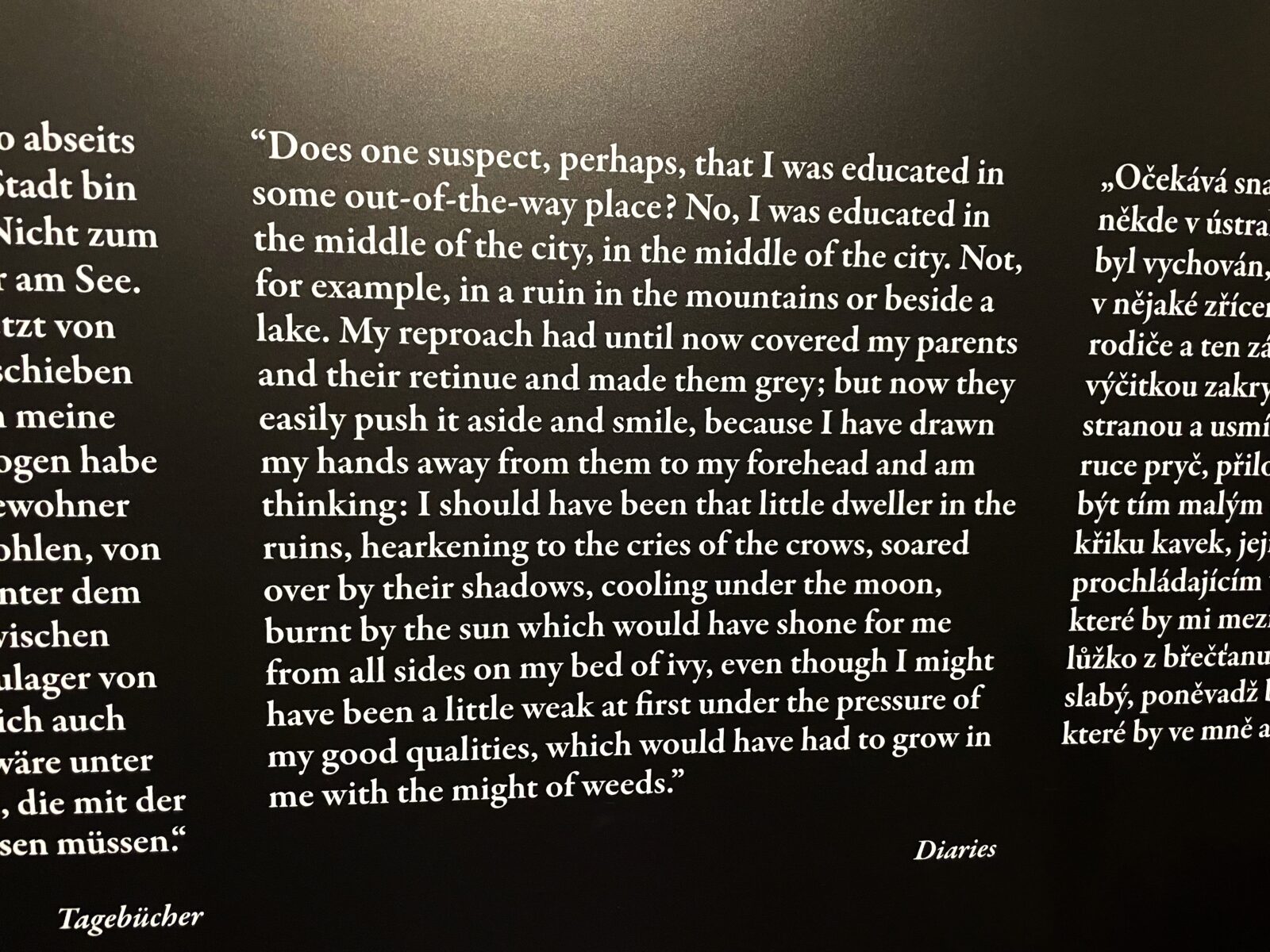

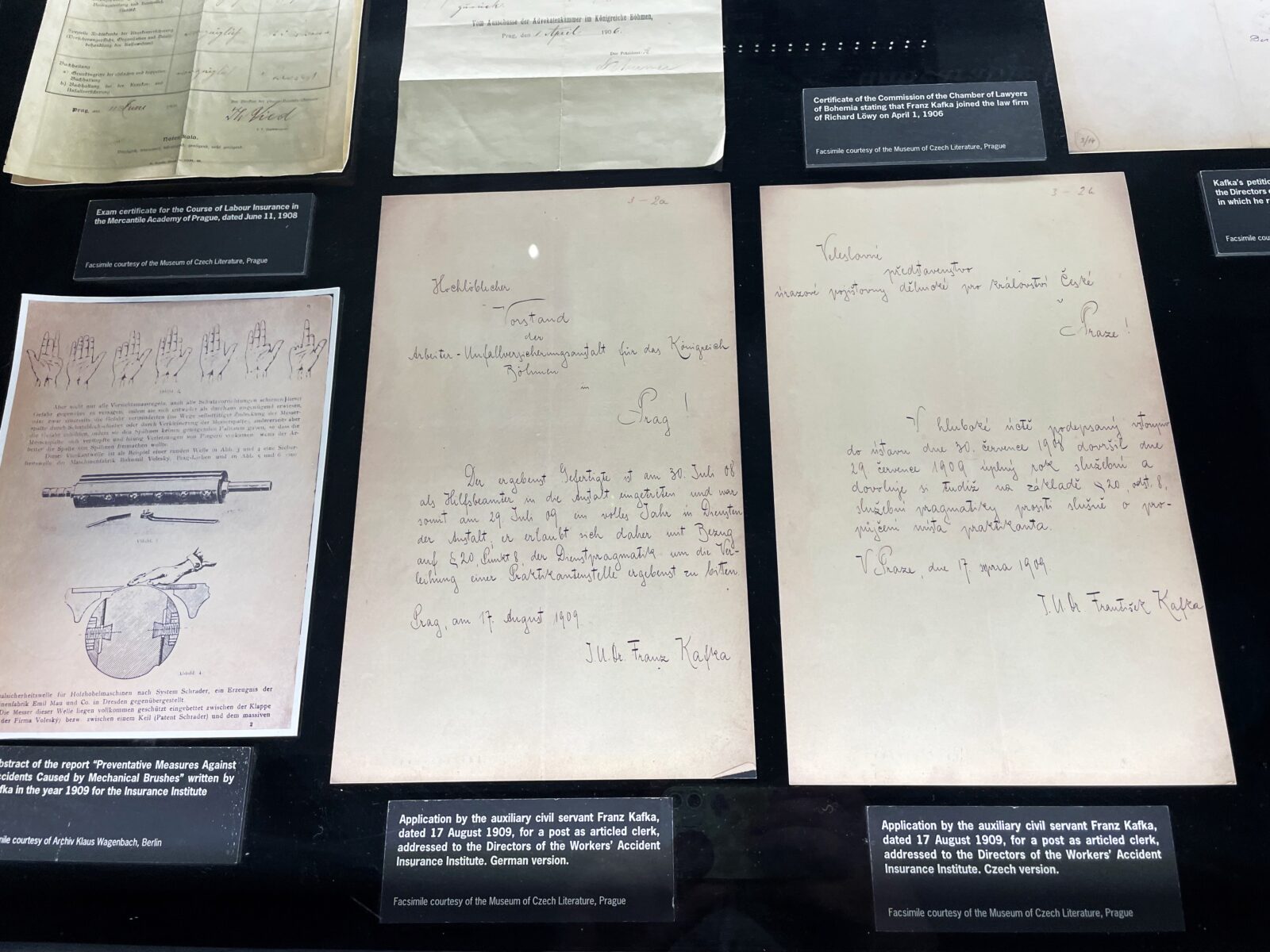

Kafka is often presented as the OG sad boy, a neurotic recluse who ordered all his own books burnt after his death, and just sort of sadly lay starving on his deathbed (he actually TB, a death sentence in the 20s). A sad-sack like some of his characters. Kavka/kafka is a kind of crow in Czech. Susan Bernofsky says “Gregor has only himself to blame for the wretchedness of his situation, since he has willingly accepted wretchedness as it was thrust upon him. Like other of Kafka’s doomed protagonists, he errs by failing to act, instead allowing himself to be acted upon. He has traded in his spine for an exoskeleton, but even this armorlike shell is no defense once his suddenly powerful father starts pelting him with apples—an ironically biblical choice of weapon.” Which isn’t true at all when you see about his actual life in the museum. He was attractive to women and engaged multiple times, gave public readings of his work, and was so good at his day job as a government Health and Safety Officer that every time he tried to quit to become a full-time writer, they begged him to stay.

“Kafka’s biggest problems were always with himself, his self-doubt, his savage self-criticism, but there were moments even at the end of his life when he was half-reconciled to some of his work”. Relatable.

His willingness to plunge in and examine that self-doubt and criticism is what makes his writing attractive to people however.

Kafka is a hard one to translate. He writes simple looking sentences, where half the words have double meanings in German, creating an unsettling, constantly shifting ambience, like something seen out of the corner of your eye, but written in a seemingly clear and simple way. As Michael Hofmann puts it “We obscurely feel, that there is something more going on in the story, something probably to do with sex or violence or families or metaphysics, but we’re damned if we know what it is.”

For example, it’s never outright stated that Gregor Samsa is a cockroach. He is an “ungeheures Ungeziefer”. A monstrous piece of vermin. An Ungeziefer is a nasty creepy crawly, what kind is vague.Everything about him is Un and wrong. You could alternatively express it as “Gregor woke up feeling like a total piece of shit”. Those double meanings.

His characters are plunged into confusing situations that nobody will quite explain to them, and punished for not understanding them: Gregor just suddenly turns into the physical cockroach form of his own self-loathing with no explanation of how it happened and everyone is angry and disgusted at him, Josef K is being prosecuted for some vague crime that nobody will quite explain to him, K the surveyor is just trying to do his job yet keeps coming up against the opaque feudal bureaucracy of the Castle and the villager’s scorn that he has somehow broken the rules.

According to Hofman: “On the one hand, it is almost always too late in Kafka: in ‘Metamorphosis’ Gregor Samsa wakes up as a cockroach; the prisoner in ‘The Penal Colony’ is already in chains in front of the sentencing-machine; Karl Rossmann has been sent to America by his distressed and disgraced parents — he is so far along in his particular ‘process’, ironically, that he is within sight of the Statue of Liberty. None of these things is going to be reversed. On the other hand, the end has not yet happened”

Here is a heavily abridged, fairly literally translated English text of the main gist of the story I prepared recently for handouts for a performance (the audio was in German). The original book is about 90k words and I reduced it down to two A4 sides/20 minutes of audio- I didn’t have room for the parts where Gregor’s boss turns up and tries to get him out of bed, and when he sneaks in to watch Grete play the violin. Read the full book for those. There is a rundown from the Guardian here of all the different English translations on offer.

When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous piece of vermin. He lay on his armour-hard back and, when he lifted his head a little, saw his bulging brown belly, divided by arched reinforcements, which his bedsheet, ready to slide off completely, could barely cover. His many legs, miserably thin compared to their usual size, flimmered helplessly before his eyes.

“What has happened to me?”, he thought. It wasn’t a dream. His room, a real human room, just a little too small, lay quietly between the four well-known walls. Above the table, on which was spread an unpacked sample collection of textiles – Samsa was a travelling salesman – hung the picture he had recently cut out of an illustrated magazine and placed in a handsome gilded frame. It represented a lady, wearing a fur hat and boa, sitting erect and raising up to the viewer a heavy fur muff in which her whole forearm had disappeared.

No matter how hard he threw himself onto his right side, he always rocked back onto his back. He tried it probably a hundred times; closed his eyes so as not to have to see his wriggling legs, and only let go when he began to feel a slight dull pain in his side that he had never felt before.

“Oh God”, he thought, “What a strenuous job I chose! Day in, day out on the road. So much pressure, and in addition I have this nuisance of travel imposed on me, the worries about the train connections, the irregular bad food, and the constant ever- changing, never-lasting, empty-hearted human interactions. To hell with it all!”

He felt a slight itch on top of his stomach, and slowly slid closer to the bedpost on his back in order to raise his head up better; and found the itchy spot covered in little white dots that he didn’t quite know how to judge; and wanted to feel the spot with one leg, but pulled it back immediately, because the touch sent chills down him.

“Gregor”, someone called – it was his mother – ,“It’s quarter past six. Didn’t you want to get away early?” That soft voice! Gregor was startled when he heard his answering voice, which was unmistakably his earlier voice, but which, as if from below, was mixed with a painful squeak that couldn’t be suppressed.

At first he wanted to get out of bed using the lower part of his body, but this lower part, which he had not yet seen and could not really imagine, turned out to be too difficult to move; it was so slow; and when at last, almost frantic, he recklessly pushed himself forward with all his collected strength, he found he had chosen the wrong direction, and was struck violently against the lower bed- post, and the burning pain he felt taught him that the lower part of his body was in fact perhaps the most sensitive at the moment.

He came to the conclusion that he preferred to stay in bed.

—-

It was only at dusk that Gregor woke up from his heavy, fainting sleep. At the door he realised what had actually lured him there; it had been the smell of something to eat. For there stood a bowl filled with sweet milk, in which little pieces of white bread were floating. He almost laughed with joy, because he was even more hungry than he had been in the morning, and immediately he immersed his head in the milk almost up to his eyes. But he soon withdrew it, disappointed.

To test his new tastes, his sister Grete brought him a whole selection of food, all spread out on an old newspaper. There were old half-rotten vegetables; bones from supper surrounded by congealed white sauce; a few raisins and almonds; an old cheese that Gregor had declared inedible two days ago; some dry bread, and some bread smeared with salted butter. He ate the cheese, the vegetables, and the sauce in quick succession, his eyes watering with satisfaction; he didn’t like the fresh food on the other hand, he couldn’t even stand the smell of it, and he even dragged the things he wanted to eat a little further away.

—-

Gregor’s wish to see his mother soon came true.

During the day Gregor didn’t want to show himself at the window out of consideration for his parents, but he couldn’t crawl much on the few square meters of floor either, he found it difficult to lie down quietly during the night, and eating soon didn’t offer him the slightest pleasure any more, and so for amusement he adopted the habit of crawling all over the walls and ceiling.

He especially liked hanging at the top of the ceiling; it was very different from lying on the floor; one breathed more freely; a slight vibration went through the body; and in the almost happy absent- mindedness in which Gregor found himself up there, it could happen that, to his own surprise, he let go and plopped onto the floor.

His sister immediately noticed this new amusement that Gregor had found for himself – he also left traces of his mucus here and there when he crawled – and got it into her head to enable Gregor to crawl as much as possible, so the furniture that prevented it, above all the wardrobe and the desk, should be taken away.

Despite Gregor telling himself again and again that nothing out of the ordinary was happening, just a little furniture being rearranged, he soon had to admit to himself that the women walking back and forth, their little calls, the scratching of the furniture on the floor, had an effect like a great commotion pressing in on all sides, and he couldn’t help but tell himself, no matter how hard he pulled his head and legs into himself and pressed his body to the floor, that he couldn’t endure the whole thing for long.

And so he burst in to the room – the women were leaning against the desk in the next room to catch their breath – and changed direction four times, really not knowing what to save first. Then he saw the picture of the lady dressed in fur on the empty wall, hastily crept up to it and pressed himself against the glass, which held him tight and soothed his hot belly. At least this picture, which Gregor had now completely covered up, would certainly not be taken away by anyone. He cocked his head toward the living room door to watch the women return.

His mother stepped aside, saw the huge brown spot on the flowered wallpaper, and before she was actually aware that what she was seeing was Gregor, she called out in a screaming, hoarse voice:”Oh God, oh God!” and fell over the sofa with outstretched arms, as if completely giving up, and didn’t move.

The sister ran into the next room to fetch some smelling salts to wake the mother from her faint; Gregor also wanted to help – there was still time to save the picture – but he was stuck to the glass and had to tear himself free; he then ran into the next room as if he could give his sister some advice, like in the old days; but then had to stand idly behind her while she rummaged through various bottles. She was startled when she turned around; a bottle fell to the ground and broke; a splinter cut Gregor in the face, and some caustic medicine flowed around him. Gregor was now completely cut off from his mother, who might have been close to death through his fault.

A little while passed, Gregor lay there exhausted, it was quiet all around, maybe that was a good sign.

His father had come in. “What’s happened?” were his first words; Grete’s appearance must have told him everything. Grete answered in a muffled voice, evidently she pressed her face against her father’s chest: “Mother passed out, but she’s better now. Gregor escaped.” “As I expected” said the father “I’ve always told you so, but you women don’t want to hear it”

It was clear to Gregor that their father had misinterpreted Grete’s all too brief message and assumed that Gregor had been guilty of some violent act.

“Ah!” the father cried out as soon as he entered the room, as if he were angry and happy at the same time. Gregor pulled his head back from the door and raised it towards his father. He probably didn’t know himself what he was up to; at least he lifted his feet unusually high, and Gregor was amazed at the enormous size of his boot soles.

So Gregor stayed on the floor for the time being, especially since he was afraid that his father might think it was particularly malicious to run to the walls or the ceiling.

As he staggered along to gather all his strength for the run, he scarcely kept his eyes open; in his dullness he never thought of any rescue other than by running – then he realised something had been thrown at him, which rolled in front of him. It was an apple; immediately a second flew after him; Gregor stopped short in terror; it was useless to keep running because his father had decided to bombard him.

His father had filled his pockets from the fruit bowl on the sideboard and was now throwing apple after apple without aiming in particular. These little red apples rolled on the ground as if electrified and bumped into each other. A weakly thrown apple brushed Gregor’s back, but slipped off harmlessly. On the other hand, the one that immediately followed painfully penetrated Gregor’s back; Gregor wanted to drag himself on, as if the surprising, unbelievable pain could pass with the change of location; yet he felt pinned down and stretched in complete bewilderment of all his senses

——

Gregor’s severe wound, from which he suffered for more than a month – the apple remained in his flesh as a visible souvenir because no one dared to remove it – seemed to have reminded even his father that Gregor, despite his present sad and disgusting appearance was a family member who was not to be treated as an enemy, but towards whom it was a family duty to swallow resentment and tolerate, (nothing more than tolerate). Now that Gregor had probably lost his mobility forever due to his wound, it took him long, long minutes to cross his room like an old invalid – crawling up high was out of the question.

In this overworked and overtired family, who had time to look after Gregor more than was absolutely necessary?

The main thing that kept the family from moving was complete hopelessness and the thought that they had been hit by a misfortune like no one else in their entire circle of relatives and acquaintances.

Dirty streaks ran along the walls, here and there there were balls of dust and rubbish. Gregor hardly ate anything any more. Only when he happened to pass the food would he take a morsel into his mouth, hold it there for hours and then usually spit it out again. At first he thought it was sadness about the condition of his room that kept him from eating, but he soon made his peace with the changes in the room. People had gotten into the habit of putting things in this room that could not be accommodated elsewhere, and there were now many of these things since some rooms in the apartment had been rented out to three tenants.

These serious gentlemen – all three had full beards, as Gregor once noticed through a crack in the door – were scrupulous about order. They would not put up with anything useless or dirty. Moreover, they had brought their own furnishings with them.

——

“Herr Samsa!” shouted the man in the middle to his father and, without wasting another word, pointed with his index finger at Gregor, who was slowly moving forward. They actually got a little angry at the realisation that they had been living with a housemate like Gregor.

“I hereby declare”, said one of the tenants, raising his hand and also looking at the mother and the sister, “that with regard to the disgusting conditions prevailing in this apartment and family” – he spat on the floor with a momentary resolute decision –”I am giving notice of my room immediately”.

The whole time Gregor had been lying quietly on the spot where the tenants had spotted him. Disappointment, but perhaps also the weakness caused by starving so much, made it impossible for him to move.

“Mother, Father”, said his sister and slammed her hand on the table,”It can’t go on like this. I don’t want to say my brother’s name in front of that Thing, so I’ll just say we have to try to get rid of it.” “She’s right a thousand times over”, said the father to himself. The mother, still unable to find enough breath, began to cough dully into her hand with an insane expression in her eyes.

“It has to go”, stated the sister, “that’s the only way, Father. You just have to try to get rid of the thought that it’s Gregor. The fact that we believed it for so long is our real misfortune. But how can it be Gregor? If it were Gregor, he would have realised a long time ago that it’s not possible for people to live with such a disgusting creature and would have left voluntarily.”

——

When the cleaner came early the next morning, she didn’t find anything out of the ordinary during her usual brief visit to Gregor. She got angry and pushed Gregor a little, and only noticed when she had pushed him from his spot without any resistance. When she soon realised what had happened, she widened her eyes, whistled to herself, but didn’t stay long, instead jerking open the door of the bedroom and calling out into the darkness in a loud voice: ‘Look, that thing has finally croaked; there it is, dead as a door nail!”

“At last”, said Mr. Samsa, “Thank God.” He crossed himself and the three women followed his example.

Grete, who never took her eyes off the corpse, said: “Look how skinny it was. It hadn’t eaten anything in a long time. The food just came out as soon as it came in” In fact, Gregor’s body was completely flat and dry, you could only really see it now that he was no longer lifted up by his little legs and nothing else distracted the view.

Then all three left the apartment together, which they hadn’t done for months, and took the tram out into the city. They sat alone in a carriage completely lit up by the warmth of the sun.

As they talked, Mr. and Mrs. Samsa, looking at their daughter, who was becoming more and more lively, almost simultaneously remembered how lately, in spite of all the troubles that had made her cheeks pale, she had blossomed into a beautiful and voluptuous girl. Becoming quieter and almost unconsciously communicating by looks, they thought that now would be the time to look for a good husband for her

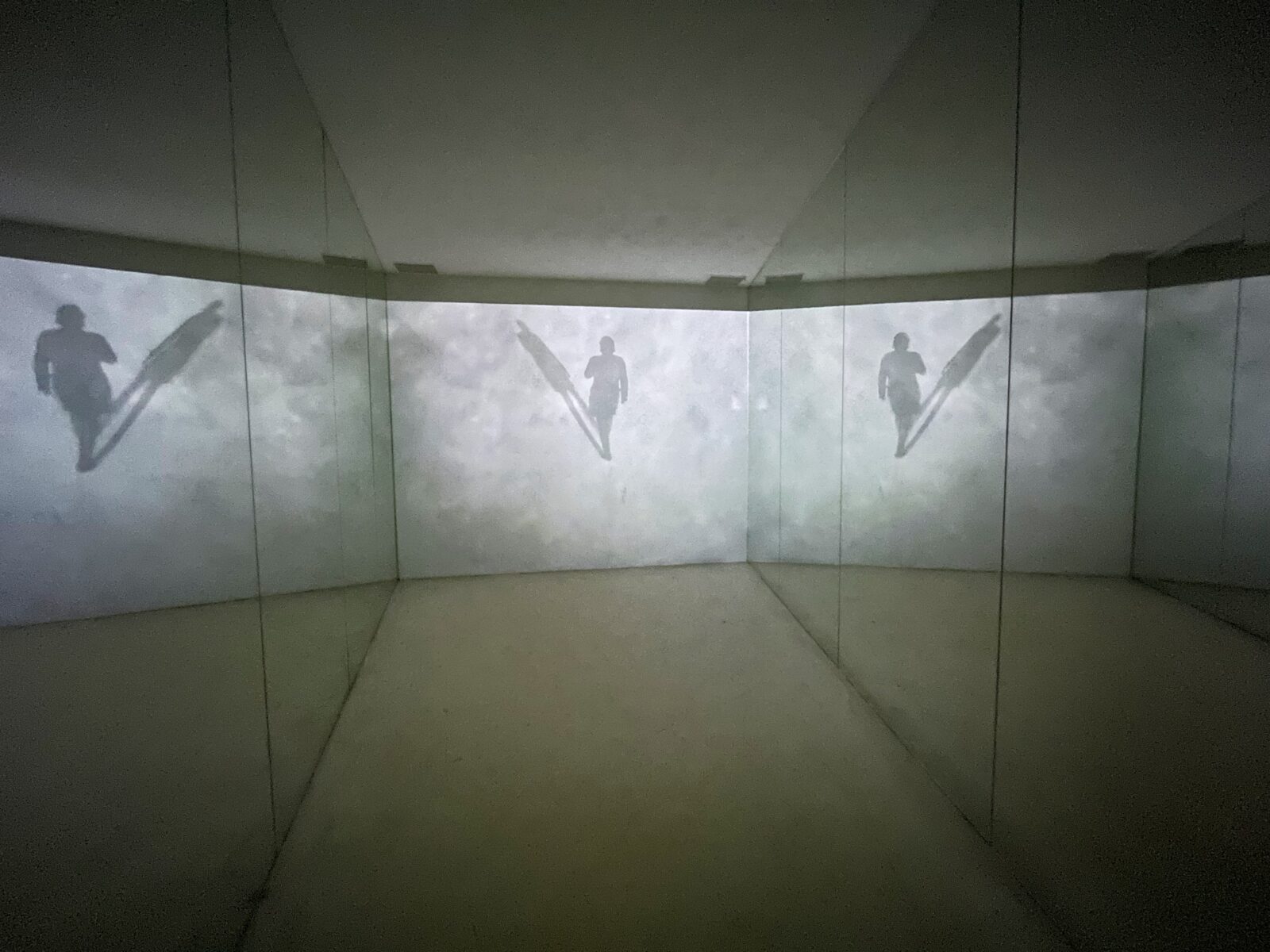

They have a loop of cinefilm of Prague in Kafka’s day. A lot of it looks like B-roll from Nosferatu.

The stairs descend you to basement hell. Aka the office.

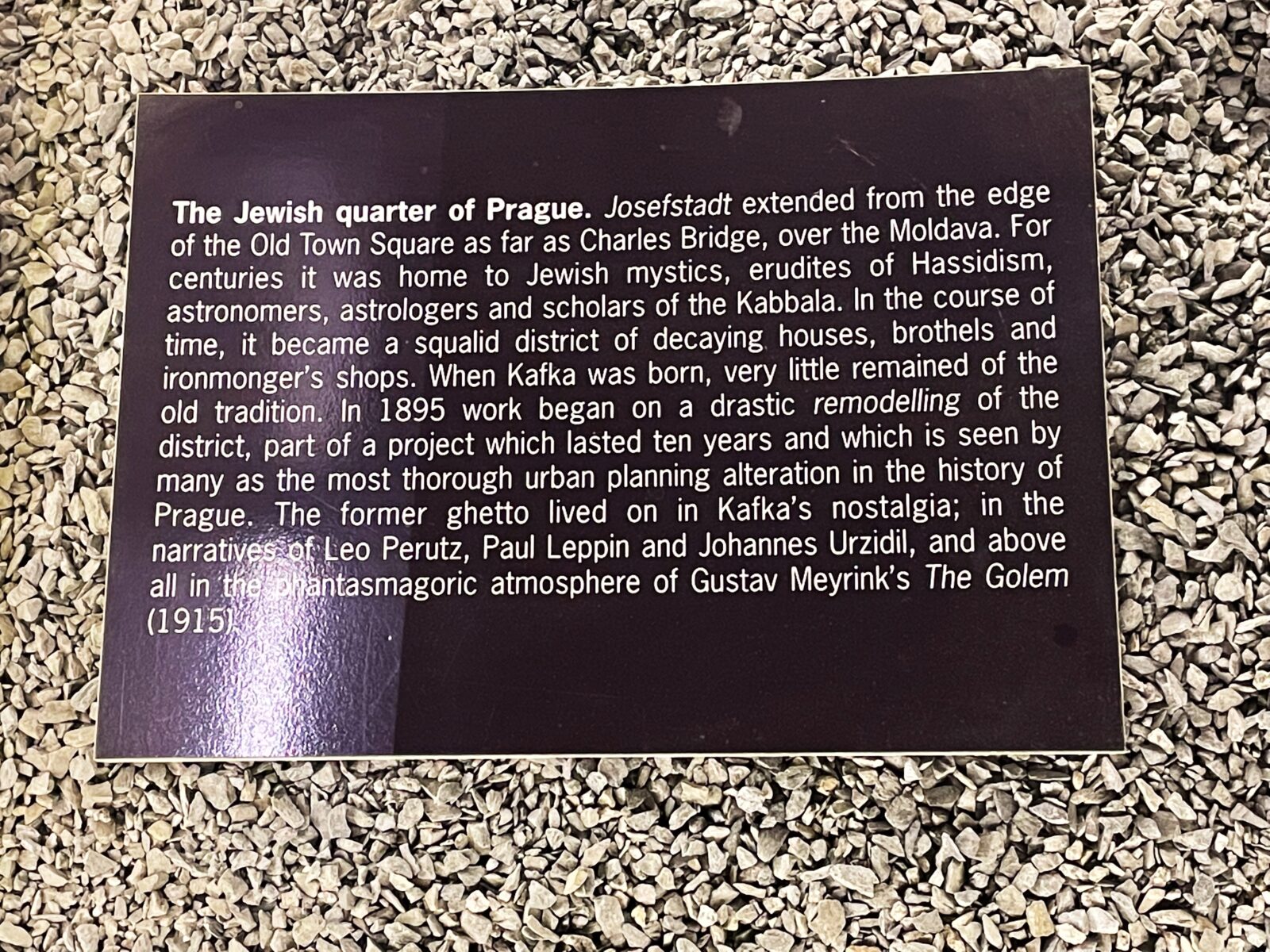

The filing cabinets lurch at you and have various different letters from Kafka to his family and various girlfriends inside.

Much needed Kafka and Mucha merch.

Leave a Reply