(Not just a cheerful travelogue- politics and history and the life and death of Stefan Zweig)

I have been in Austria for a week and a half now for teaching work. I meant to update last week, but some brutal 7.30 am start times, heavy snow, a lot of planning to do outside the classroom, and a diet of pure stodge in a small town with few dining options (and even fewer options for vegetarians) tired me out. It feels strange to be in small-town Austria, where not much tends to happen, while political turmoil with dire consequences for many vulnerable people goes on around the world.

The UK does not feel like a good place to be right now, but I can’t stay away forever. I will not be back for more than a few days until April at the earliest anyway. I’m now in Steiermark, the start of the Alps, and the snow is all gone, and there is rain much the same as an English winter. For my job I get sent to run workshops in schools in towns few tourists visit. Apart from next week in Vienna, I’m criss-crossing Austria on the train to various small towns dotted around. I enjoy lengthy solo train trips in the mountains with suitable music and snacks, but I don’t enjoy lugging a suitcase filled with 5 weeks worth of supplies, even if it does have wheels.

When people picture Austria, they have an image of Vienna, elegant, full of opera houses, art museums and slightly kitschy Mozart souvenirs, and the Alps, full of charming wooden chalets, drifts of powdery snow, and hearty people in lederhosen (and probably adding an imaginary background of mountains to Vienna).

The east of Austria (where Vienna is) is actually mostly flat. I’ve been in Vienna overnight two Saturdays in a row now, but was either at a work training event, or leaving early the next morning for further travel. I’ll be there for a full week from Sunday anyway and will take full advantage of my afternoons off to see some exhibitions. I have been to Vienna many times before, and frequently at times of year with better weather.

There’s something a little bit low-key seedy about Vienna outside of the grand buildings on the tourist routes (although it is a very safe city). Run-down little shops that seem to have been there forever, rotting art nouveau stations with no staff on the green Ü4 line, decrepit looking branches of Norma and Pennymarkt supermarkets with peeling beige lino tiles and flickering neon lighting that make Lidl look luxurious and which close on the dot at 6pm. Indoor smoking is still legal (and very prevalent). The Danube is not as central as you might expect. German TV often picks a Vienna accent for small-time crook characters. There’s the Vienna schmäh, the mix of charming manners and snide humour. And the (increasingly familiar) accent, where people mumble yet draw out the vowels at the same time.

Last year I read The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig, the memoir by the Austrian writer who was an international star between the wars until his persecution by the Nazis (and topic of this weirdly personal bit of vitriol by Michael Hofmann here). He had been neglected until lately in the UK, until the release of the Grand Budapest Hotel (loosely based on several of his stories) caused his books to be reissued, and in particular The World of Yesterday to be translated by one of my favourite translators, the incomparable Anthea Bell. The World of Yesterday covers his upbringing in 1890s Vienna, the shock of the First World War and the rise of Fascism, and ends with his escape to Brazil (and eventual suicide).

Stefan Zweig discusses how in fin-de-siècle Vienna, discussion or education about sex was forbidden, yet brothels and porn were everywhere you went. Boys at his school were barely allowed to speak to girls their own age, yet got themselves into terrible anxieties by leaving their wallets (with their ID card inside) in brothels and dreaded being blackmailed that the managers would tell their parents. No wonder this was also the era of Freud and Kafka, and psychoanalysis, As an adult in the 1930s, he’s absolutely relieved that aspect of the era is over. No-one cared about sports or football, teenagers were obsessed with actors and poets, and poets were like rock stars. As a respectable secular Jewish family in Vienna, the Zweigs felt comfortably accepted in society- these things can change or be changed any minute.

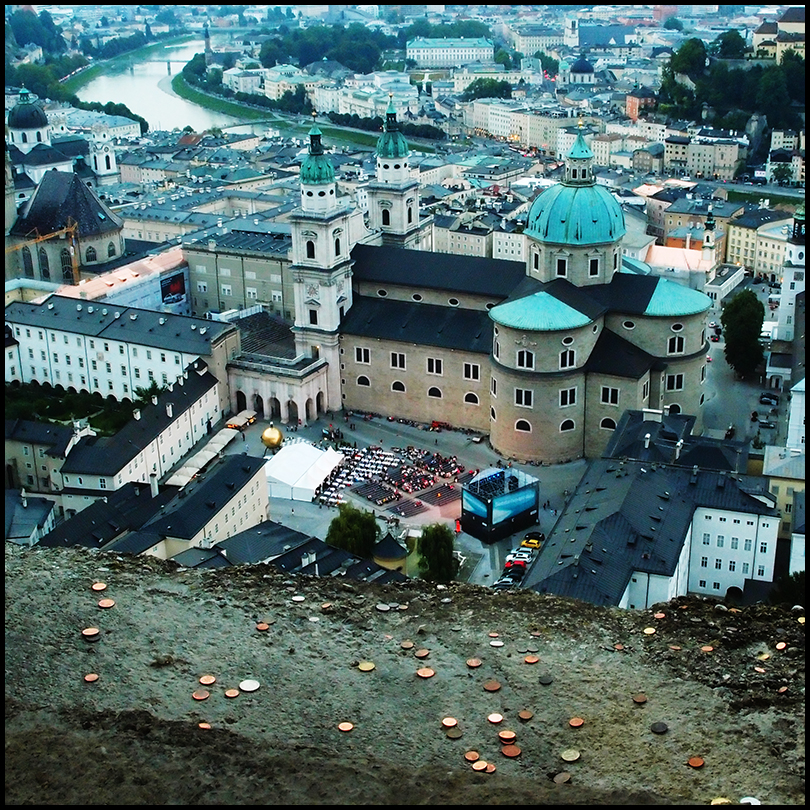

After the Anschluss, and the increasing restrictions on Zweig, the fact that he could practically see Hitler’s house in Berchtesgaden from his own house on a mountain outside Salzburg only rubbed it in further. His success and international respect as a writer could do nothing to change it, and he and his wife ended up having to leave Austria for Brazil (via the UK and USA). Being a German-speaking writer, whose work was eventually banned in every country that spoke his language, and an internationalist who now could barely visit or communicate with any of his writer friends dotted across Europe drove him to despair.

Something that also sticks out in the current political climate of increasing nationalism, calls for closed borders and countries turning away Syrian refugees, is Stefan Zweig’s (and others) utter outrage at the closing of national borders and introduction of passports in WWI. Until then all borders were open, and anyone could travel anywhere, and passports and border controls felt like a loss of freedom and a scary imposition of control (for the record, I am 100% pro open borders).

“‘People went where they wished and stayed as long as they pleased. There were no permits, no visas, and it always gives me pleasure to astonish the young by telling them that before 1914 I travelled from Europe to India and America without a passport and without ever having seen one’. The Great War and its aftermath increased what Zweig calls ‘a morbid dislike of the foreigner, or at least fear of the foreigner…. The humiliations which once had been devised with criminals in mind were now imposed upon the traveller, before and during every journey. Thereafter, everyone required official photographs, certificates of health and vaccination, letters of recommendation and invitations, and addresses of relatives and friends for ‘moral and financial guarantees’ … His Austrian passport became “void,” as he puts it after the Anschluss, the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. He was forced to ask British authorities for an emergency white paper, ‘a passport for the stateless’. He came to understand what an exiled Russian acquaintance had once told him: ‘Formerly man had only a body and a soul. Now he needs a passport as well for without it he will not be treated like a human being’..” (from this article)

Leave a Reply