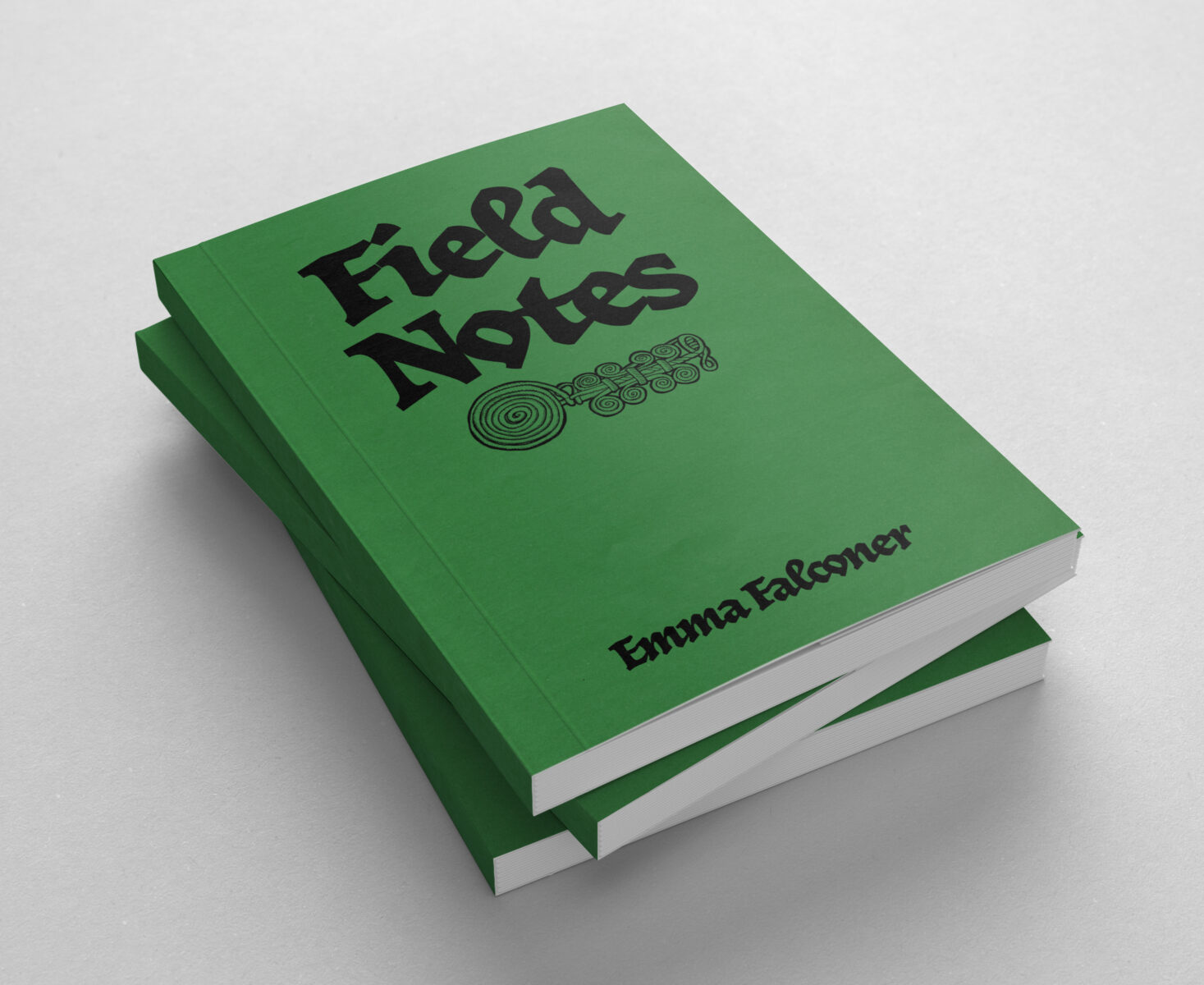

I have a new book project out early 2026. Fiction this time! A novella set in Bronze Age Kent.

Beaker People, time-travel weirdness and (historically accurate) stone circles.

200 page paperback on luxury paper, with illustrations. UK shipping is free.

Here’s a sample chapter…

Chapter One

I am in entirely the wrong place. I was supposed to be researching political pamphlets in seventeenth century London, but instead I am here. I don’t know when or where here is now. I am in a wood, and that wood could be in any time or place. I just know I’m not in the present day or the time I’m supposed to be.

Time travel is real, but it’s not how people expect. There are no time machines or mad scientists or dramatic flashes of light. When the time is right you just slip through the thin places between the here and now. There are no instruments that can spot these places, they give off no particular signal that scientists can pick up, you just have to learn how to see them. Where you can go to through them is extremely limited however. The thin places always lead to the same destinations, and a limited range of times within then. In the UK we have an easily accessible door to London in 1668. If you stay to the end of December it just loops you back round to mid March. When you enter, you’re never quite sure what month you will arrive in, but it doesn’t matter too much, because it’s such a limited range. It’s disconcerting at first, but everyone on the project is used to it by now. The door itself isn’t actually located in London, it’s on an industrial estate in the Midlands. None of the handful of others we know of around the world lead to the same place they’re situated in. It seems to be some kind of wormhole effect.

I am an academic working for a research institute that sends suitable historians and anthropologists through to research Restoration London. I guess technically I shouldn’t be writing this, because I signed the Official Secrets Act, but at this point that seems fairly meaningless. Only people who have completed exhaustive rounds of training and have a suitable academic grounding are allowed through. No tourists. No military. You could seriously mess things up if you didn’t respect the period. Only next of kin know where you really are on your “work trip”

The Institute approached me because of my work on pamphlet publishing in seventeenth century England. Cheap printing and increased literacy caused an explosion in publishing, with leaflets sold for pennies from stalls on the street, fiercely arguing for and against anything and everything, and giving ordinary people access to the words of writers like Thomas Hobbes and Jonathan Swift. My first project was to spend a week simply being a customer, buying a selection of pamphlets that hadn’t survived in modern archives, and mapping out the locations and relationships of the stalls and booksellers without engaging with anyone too heavily.

I didn’t know what month I would arrive in London, but it was all arranged that I would go to the Institute’s safe house on Cheapside to meet Helen and Rajesh, and then Helen would go back. We never leave anyone stationed alone in the field.

Rajesh has been having the time of his life pretending to be a fabulously wealthy textile merchant operating out of Isfahan at the height of its early modern glory. He is ostensibly there in London to buy the finest brocades. In his quest for the best, of course he has to meet all the Huguenot weavers and tour all the workshops around Spitalfields, and spend the Institute’s money on bolts of the finest cloth. They would probably be disappointed to find out that he’s actually from Neasden, which is just a small village in that era.

He at least has a solid historically researched persona to back him up. There were plenty of Gujarati merchants in Persia at this time, and on the small chance that he ran into one of them in London he’d be able to bluff his way through it as long as they didn’t ask too many detailed questions about where his hometown was or who he was related to.

I on the other hand right now am a woman pushing sixty dressed as a generic labourer from the 1660s. We’ve found that it helps to ward off sexual harassment on the streets and markets, and people in that era go by clothes as much as anything. If you’re dressed as a nondescript man with nothing worth stealing, they pay you no attention. Many men had longish hair at this time, so stick a shabby looking hat on and nobody will look at your face too closely. This was supposed to be my first trip, so I had no established persona or contacts in period yet.

Initially we were very cautious and all staff in the field made sure to be inconspicuous and anonymous background observers. However it turns out the Butterfly Effect doesn’t seem to occur (that we know of). History hasn’t changed at all from the perspective of anyone in the field or outside it. Or if it does, it changes all of our memories and material evidence so thoroughly that nobody notices. There’s also a strange effect where if you go through the loop a few times and get to know people a little, when you come back round to an earlier time than your initial meeting, they don’t remember you consciously as such, but have some kind of subconscious positive reaction to you, so it’s easier to re-introduce yourself each time. So this leaves us free to run more involved projects like Rajesh’s. The effects of staying in the field for too long, whether on physical or mental health, are unknown. It’s a risk we have to take. So staff are rotated, with no permanent stationing and as little time in the field to carry out their research as possible. So far there are only five of us with the requisite training, and I am the newest.

We are still very careful what items we bring through. No plastics, no aluminium, no electronics. Nothing from technologies that have not been invented yet. No zips or metal snaps. Clothes and possessions are carefully researched to fit into period as closely as possible, and not stick out as desirable to steal. I was very pleased with the leather knapsack I found that looked just like one I saw in a Dutch painting. Everything we bring is marked with the Anachronism Mark, to not throw the work of future historians. As an experiment, we have tried radiocarbon dating objects brought there and back, and it doesn’t seem to affect the readings especially. At least no more than volcanic eruptions or the Industrial Revolution ever did.

We have some little spy cameras disguised as cheap snuff boxes, loaded with orthochromatic monochrome film, which was outdated even by the 1920s. It doesn’t give the best renditions, but it survives the journey better. Colour film ends up completely warped and almost completely orange. Modern black and white film fares little better, and ends up fogged. There’s something about how the older film doesn’t pick up reds very well that helps it survive better. Mostly however we rely on drawings and observations written in our field books.

I had carefully selected this notebook with its crude wrap-around leather cover to look as period appropriate as possible. Ironic considering I don’t even know what period I’m in, and might be walking around with it before the invention of writing or paper. The notebook was supposed to contain my academic field notes from the research project, but I guess it can serve as a diary. I don’t know if anyone will ever read it, but perhaps writing it will preserve my sanity. Maybe there is nobody here who can read. At least if that’s the case, I will never have to spell my name out again. S-H-E-L-A-G-H. No, not “Sheila”. No thanks to my parents who are not even Irish, they just thought it was a more romantic spelling.

When you come through the gap, it’s supposed to feel both instantaneous and like a long walk all at once. If you focus right, you arrive smoothly, slotted into your new time stream. This is not how it felt. I walked between the planes of the air, but there was a strange snagging resistance. I thought it was due to my inexperience, but now I know either my technique was wrong or there was some other factor we’re not aware of. When I emerged, I was alone in this wood rather than in a back street of London. When I tried to go back through, there was no opening. I was stranded, alone.

I suppose I can sit and cry under a tree in the Stone Age or wherever I might be, but it won’t get me anywhere. I should at least try to use my brain. Once the initial panic swelled down a little, I looked at my surroundings to try to gather some clues. Deciduous woodland with an assortment of trees. Temperature around 15ºC. Nowhere tropical. It seemed to be somewhere in Northern Europe on a spring afternoon. Or maybe New Zealand? I remembered something about the shadows being the opposite direction in the Southern Hemisphere. That didn’t seem to be the case here, or maybe I was looking at it wrongly? These were all familiar kinds of tree anyway, and in New Zealand they would probably be different ones. Maybe lots of ferns? I’m going to go with Northern Europe.

I wish I were the kind of person who could look at some tree bark and immediately go “ah, it’s the fifteenth of April, we are at 52ºN and the hawthorn is about to bloom”, but sadly I’m not. I’ve spent years in archives going through historical paperwork and speaking at conferences. I’ve received every vaccination for historical diseases known to man, and been trained to spot the initial signs of bubonic plague, but I’m not qualified to live out in the woods in some undetermined historical period. I wish I had watched more Ray Mears shows. I used to tease my husband when he would watch them all the time, but I wish I had paid more attention.

Thinking about him was already making me feel sad when the jetlag and nausea hit, and I found myself copiously vomiting into the leaf mould while my head span. They had warned us that this could happen, and we had practiced breathing and focus exercises to centre our nervous system on the time we had travelled to. The problem was that I wasn’t in that time, and my brain didn’t know where I was or what to centre on. I can feel that it’s not the present day, there’s a sense that’s hard to explain. But I also know I’m not in the time I was locked onto, and I have no feel for whether I’m in the past or future or what. Perhaps I’m in some kind of Riddley Walker type post-apocalypse future where people have returned to the wild. I don’t have any wilderness survival training. The best I can offer is a few camping trips to the Peak District years ago. I’m an expert in seventeenth century political pamphlets. This is entirely the wrong period. I have no training or qualifications in this. Maybe there are no people here because it’s too early or too late. Even if there are, turning up dressed up as a seventeenth century peasant with a keen interest in the latest court gossip isn’t going to help me any. I don’t know what I’m going to do.

I don’t have any food apart from some backup protein bars (fresh food tends to shrivel up on the journey, nobody knows why) and I don’t have a tent because I was supposed to be staying at the safe house, and anyway a tent would be useless in London. I have a blanket rolled up around my bag, some water purification tablets and first aid bits disguised in fake historical packaging, a fire kit with a flint and metal striker, and a parcel full of bars of soap to restock the safe house. I’m thankful for the soap. It’s one of the few everyday essentials we don’t buy in period, because imported olive oil soap is expensive and hard to find, and experience has taught us that the local tallow-based product is grim. It’s all well and good attempting to live in a historically accurate fashion, but it’s no good if you give yourself dysentery in the process or waste all your research time trying to find somewhere to get hold of decent soap.

The heavy reality of my situation slammed into me along with the nausea. I wanted to run, I wanted to scream, but the best I could do was cling onto a nearby tree in a pathetic kind of way while I slumped onto the ground and felt myself becoming completely unmoored from the world.

Leave a Reply